A private equity puzzle

Private equity occupies a special place in the universe of investment alternatives. A nascent asset class only decades ago—at which point public equities had existed in their modern form since at least 1602*—the industry has grown substantially in size over time. Simple anecdotes illustrate the incredible stature the industry has achieved since its early days:

Today, pension funds around the world scramble to ‘get an allocation’ to the most highly regarded funds;

Scions of the industry regularly wax philosophical to a very friendly business press about ‘what it takes’ to be a great entrepreneur (and are listened to), or even have their own programs discussing their views on the world with notables like Secretaries of State and are held out as “peers” of said notable people;

Other former scions have run for high office, with at least one running for the highest office, with his experience in private equity occupying a central place in the narrative around his competence as a leader, and the central focal point of attack for his opposition;

Like clockwork, many of the best and brightest young minds at the world’s best collegiate institutions are motivated by (among other more innocuous things, like learning, etc., it should be said) the chance to eventually land in private equity in making a Faustian Bargain in which they will first spend 1-2 years enduring a job that in certain instances has been so unnecessarily stressful (M&A investment banking) that a non-negligible number of those in its employ die either from acts of self-harm or exhaustion;

There are now eager start-up private equity funds aiming to bring private equity investment opportunities to retail investors. Here is one such exemplar fund that, ironically, is funded by private equity.

But is this stature deserved? And, if it ever was, is it still today?

At the outset, it’s worth noting that many credible people have long said “no” to that question. Take Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, for example. His main qualm about the industry, reportedly, is that it is full of rent-seeking, e.g., the extraction of wealth from the economy to the benefit of the funds without an equal creation of incremental economic value. The steady stream of stockholder litigation involving private equity funds as defendants would seem—at a minimum—consistent with that assertion, even if you think many of these suits are frivolous efforts at rent-seeking in and of themselves.

Another relevant economic question is whether the industry’s returns are even that good.

A review of the returns of at least one of the most well-respected and prestigious private equity firms over the past several decades suggests the glory days might be over. In the case of that firm (who shall go nameless here), annual equity returns over the last 40+ years were about 50 percent, but only about 30 percent over the last decade+ or so, implying a near halving of annualized returns from its first three decades (when returns must have averaged a little over 57 percent) to the most recent decade for which I have data (which actually ended a few years ago). If you do a simple monthly trendline through these numbers using the exact dates in the data, it would suggest annual returns for the period ending this month are probably about 18 percent. Now, 18 percent per year sounds pretty good, but keep in mind that typical private equity investments are super leveraged, and leverage creates mechanical volatility. There is nothing all that special about that, because anybody can do it. De-levering the illustrative 18 percent equity return assuming 60-80 percent leverage implies the asset return for the firm is only about 4-7 percent. Nominal US GDP growth isn’t too far below that (~3 percent/year for 1948 to 2021) and easily-constructed portfolios of public equities commonly achieve growth at that level on a leverage-free basis.

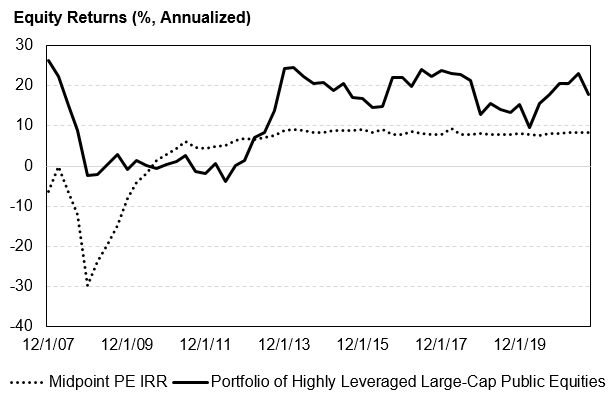

This is just one example, so it’s probably worth looking at the data more comprehensively. The chart below is a stab at that. I put this together pretty quickly, so take it with a grain of salt and as simply a conversation-starter (like everything else on this blog/site). The dotted line is the mid-point of the 2nd- and 3rd-quartile internal rates of return (IRR, or annualized equity return) of private equity funds in Bloomberg’s database. The solid line is the trailing five-year compound annual return of a portfolio of the 20 S&P 500-constituent stocks with the highest total debt/market capitalization, re-balanced monthly (i.e., it assumes that, each month, you re-rank the stocks in the S&P 500 index on the basis of total debt/market capitalization and select the top 20, selling any that have fallen out of the top 20 from the prior month and buying any that have entered the top 20). For the solid line, I’ve excluded financial institutions, since many of these have higher-than-even-private equity-level leverage and casual observation suggests they typically aren’t a focus for most private equity investments. I’ve used a five-year trailing return for the solid line as that is commonly suggested as a target holding period for private equity investments. The data for the solid line are from FactSet.

Both lines in the figure have the same general shape—there is a big decline in the aftermath of the financial crisis, followed by a strong improvement and subsequent consistency in returns. It is striking, however, how much higher the returns of the public equity portfolio are at most points in time. Over the whole period, the average is 3.7 percent for the private equity IRRs and 12.7 percent for the public equity portfolio. The implied annualized Sharpe ratio is 0.4 for the private equity line and 1.3 for the public equity line.**

Just to make sure my half-baked analysis isn’t directionally wrong even if is lacking in perfect rigor, I did a brief scan of the relevant literature and, sure enough, others who have studied this have said much the same thing. Bain & Co, along with HBS professor Josh Lerner, for example, recently found that “US buyout [i.e., private equity] returns have converged with public equity returns over the current cycle, closing a three-decade gap in performance[.]”

So what is going on? Surely, many things are, but I suspect one basic economic factor is key: competition. In the long run, competitive markets eliminate persistent abnormal excess profits such that the expected return on invested capital equals the cost of capital. There is nothing controversial about this concept. When a business arises that appears to crush it, new entrants soon follow, and competition whittles away the “excess” profits. After Uber came Lyft, after VRBO came AirBnB. The history of commerce is replete with easy-to-come-by examples. There is a hard constraint at 0 percent “excess” returns, because if the return on capital persistently falls below the cost of capital, competitors simply exit that line of business, so there is convergence toward the level of returns that is “just high enough” to fairly compensate the production inputs (labor, capital).

As it relates to private equity, stylized facts support this story. It was probably easier to find stable, cash-generating businesses whose owners were ready to cash out at less-than-full price back in the hey dey when there weren’t 200 other funds knocking down the door and investment bankers calling the owners every day and pitching their sell-side services. Since that time, private equity has grown a ton, with hundreds (thousands?) of new firms. Annual investor commitments to private equity funds in aggregate swelled from a rounding error in 1980 to almost $250 billion in 2019, with private equity assets under management in the same period rising from probably something less than $50 billion to over $1.4 trillion. As that happened, the average multiples paid in private equity buyouts rose from ~8x (enterprise value/EBITDA) in 1990 to something closer to 12x on average in 2019, according to Morgan Stanley. All of this is consistent with an increasingly competitive market, where the modal player really isn’t adding any value, even if there is still room for the best-of-the-best to outperform.

If that’s true, the obvious question is why do investors pay pretty substantial management and performance fees for exposure private equity if it’s not that much better on average than much cheaper-to-access public stocks. It’s not all that clear to me, but the theory of “conspicuous consumption” comes to mind. Private equity holds itself out as pretty prestigious and pretty smart. To date, we have all kind of accepted that story as true unquestioningly, and people want to be a part of that probably for the same reason people buy luxury goods in general. Perhaps we need a new theory of conspicuous investment.

Notes:

*Of course, private equity in the literal sense of private ownership of businesses existed long before even the 17th century and probably has always been the dominant legal form for commercial entities. Here, I am focused on “private equity” as the term is popularly used today, referring to private investment funds (as defined by the SEC) under an institutional arrangement that typically involves general partners managing day-to-day operations and investment decision-making and limited partners that contribute additional capital.

**Caveat emptor for the data nerds: these time series averages and Sharpe ratios are contaminated a bit by the fact that they embed overlapping periods. I also haven’t measured the Sharpe ratio in terms of excess returns above the risk-free rate, so it’s not theoretically perfect, but the risk-free rate was ~0% in most periods shown in the chart.