A bubble in private markets?

I will go out on a limb and say that if there is one thing upon which the esteemed minds of empirical asset pricing agree, it might be that high ratios of market value to earnings (or cash flow, or book value, etc.) predict relatively lower subsequent returns (see, e.g., here). High valuation ratios don’t prove a bubble, of course, but they do offer a good place to look.

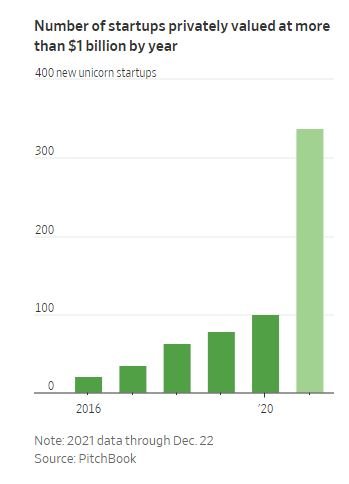

With that in mind, I was struck by the chart below from todays WSJ. Keep in mind, so-called “unicorns” often have de minimis earnings and cash flows, so the chart below may well be showing undefined or infinite valuation ratios, increasing higher still this year.

Are startups this year really worth that much more than they were last year? And if so, why startups? I haven’t put together a comparable chart examining public equities, but I suspect it wouldn’t look like this, with about 3.5x as many firms worth more than $1 billion than last year.

Is it more likely that the valuations captioned below reflect a rational pricing of expected cash flows and risk, or that some combination of chicanery and irrationality has funneled a ton of money into “growthy,” “tech-enabled” companies?

Anecdotally, I’ve been shocked at the amount of money I’ve seen raised (by people I know firsthand, no less!) for what seem like, at best, “OK” business plans. A relatively well-known venture capitalist active in this market once told me, “there’s no shortage of ideas [in Silicon Valley]. There’s just not enough execution.” One wonders if that might explain the chart below: there is a lot of money out there, and the money follows and prices the available “execution talent” in circulation. But good execution is hard to find, and when there is too much money chasing scarce good execution, the price of execution in general should rise, provided there is uncertainty about who the “good executors” are (or what the good “ideas” are). This is really just basic inflation dynamics, but with the pernicious influence of extra uncertainty: payoffs a long time in the future, obscure valuations not marked-to-market on a minute-by-minute basis (unlike public equities), and the promise of accessing investments “ordinary” investors can’t.

If this reasoning sounds fanciful, just recall that WeWork raised $13 billion from the most sophisticated investors on the planet on the back of its “community-adjusted EBITDA” before its valuation completely fell apart ahead of its initial stab at a public offering.

From Ramkumar, Amrith, and Eliot Brown, “The $900 Billion Cash Pile Inflating Startup Valuations,” Wall Street Journal, Dec. 27, 2021.